Ahh ~

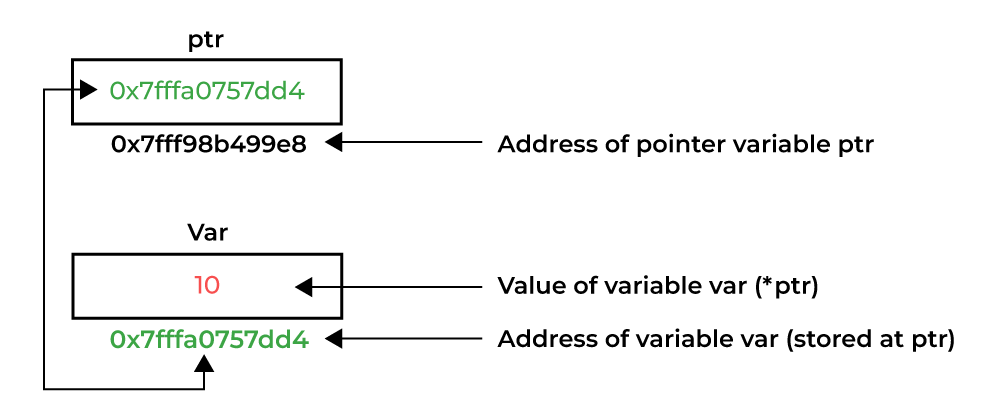

Hola, systems programmer. You've seen the tutorials that stop at int* p = &x;. That's the shallow end. We're going deep-sea diving into the memory map. Pointers are the fundamental abstraction that bridges your high-level logic with the raw, byte-addressable silicon of the machine. They are the source of your most arcane bugs—use-after-free, dangling pointers, buffer overflows—but they are also the only tool for true high-performance computing, custom data structures, and direct hardware manipulation. We're not just looking at the *, we're looking at the why. Forget the kiddie pool; this is the abyss.

|

| Image Source: GeeksForGeeks |

Secret 1: Pointer Arithmetic is Scaled, Typed Arithmetic

The first trap for the uninitiated is to see

p++ and think it means "add 1 to the address stored in p." This is fundamentally incorrect and misunderstands the core contract between the programmer and the compiler. Pointers are strongly typed for this very reason. The type of the pointer tells the compiler the size of the data it points to. All pointer arithmetic is automatically scaled by this size.When you have

int* p; on a 64-bit system where sizeof(int) is 4 bytes, the expression p++ is not translated to p = p + 1. The compiler translates it to p = (int*)((char*)p + sizeof(int)). If p was pointing to address 0x7FFF5FBFF8AC, after p++, it will point to 0x7FFF5FBFF8B0. If you had a MyStruct* s_ptr; where sizeof(MyStruct) is 32 bytes, s_ptr++ would advance the address by 32 bytes. This is the magic that makes array traversal possible. The clean, beautiful syntax arr[i] is nothing more than syntactic sugar for *(arr + i). The + i part of that expression is, in reality, a scaled offset calculation: address_of_arr + (i * sizeof(element_type)). This is why you can iterate over contiguous blocks of any data type with the same simple + operator.Secret 2: The

void* is the Type-Agnostic Primordial OozeThe

void*, or "generic pointer," is a special type that is just a raw address. It points to something, but the compiler has been explicitly told to forget what. It holds an address, but it has no associated type, and therefore no sizeof(). This makes it a powerful tool for C-style generic programming but also a dangerous one. You cannot dereference a void* directly (e.g., *my_void_ptr) because the compiler has no way to know how many bytes to read from that address: one (a char)? Four (an int)? A thousand (a struct)?This is why

malloc(1024) returns a void*. The heap allocator doesn't know or care what you plan to store in those 1,024 bytes. It just reserves the block and gives you the starting address. It is your responsibility to cast that void* to a concrete pointer type (e.g., int* my_array = (int*)malloc(100 * sizeof(int));) to inform the compiler of your intentions. This "imposes type" onto that raw memory. You also see void* used heavily in generic C library functions, most famously qsort. Its comparison function prototype is int (*compar)(const void *, const void *). It takes two generic pointers, and inside your custom comparison function, you must cast them back to your actual data type (e.g., const int* a = (const int*)p1;) to perform a meaningful comparison.Secret 3:

**p (Pointers-to-Pointers) are for "Pass-by-Reference" EmulationThis is the concept that melts brains, but it's built on a simple, iron-clad rule: C is always pass-by-value. When you pass a pointer

int* p to a function, you are passing a copy of the pointer. That is, you are passing the address it holds, by value. The function gets its own local variable, a copy of that address. If you modify this local copy (e.g., p = (int*)malloc(...)), you are only changing the local copy. The caller's original pointer remains completely unchanged, leading to a classic memory leak and a NULL pointer on the caller's side.So, how do you allow a function to change the caller's pointer? You must pass the address of the caller's pointer. And what is the type that holds the address of an

int*? An int**. This is how C emulates "pass-by-reference" for out-parameters.

// Note the 'p_to_p' (pointer-to-pointer) argument

void actually_allocates(int** p_to_p) {

// We dereference 'p_to_p' ONCE to get to the *original*

// 'my_ptr' variable from the 'main' function's stack.

// We are now modifying the caller's variable directly.

*p_to_p = (int*)malloc(sizeof(int) * 10);

}

int main() {

int* my_ptr = NULL;

// We pass the address OF our pointer 'my_ptr'

actually_allocates(&my_ptr);

if (my_ptr != NULL) {

my_ptr[0] = 5; // This works!

}

free(my_ptr);

return 0;

}

This is precisely why

main's argv is a char**. It's a pointer (*) to a list of other pointers (*), each of which points to the first char of a null-terminated string. It's an "array of strings" in C-speak.Secret 4: Function Pointers Enable Runtime Polymorphism

Variables live in memory (stack, heap, data segment), and executable code for functions also lives in memory (in the read-only

.text or code segment). If it lives in memory, it has an address. If it has an address, you can create a pointer to it. A function pointer stores the memory address of the start of a function's executable instructions. This allows you to treat functions as data: you can store them, pass them to other functions, and call them dynamically at runtime.The syntax is notoriously "nerdy":

return_type (*pointer_name)(argument_types);. For example, int (*op)(int, int); declares a pointer named op that can point to any function returning an int and taking two ints. This is the mechanism behind C-style callbacks. It's how you tell qsort which comparison function to use. But its most powerful use is in creating dispatch tables. Instead of a massive switch statement (which can be O(n) in a bad compiler), you can build an array of function pointers. An incoming command, cmd_id, can be used as a direct index into this array (dispatch_table[cmd_id]()) to call the correct handler in pure O(1) constant time. This is a foundational technique for building high-performance state machines, interpreters, and plug-in architectures.Secret 5: The Modern C++ Secret is RAII (and No Raw Pointers)

After mastering all that complex, dangerous, raw pointer manipulation, the ultimate "nerdy" secret of modern C++ is to never do any of it. The C++ Core Guidelines are clear: do not use

new and delete (and especially not malloc and free). Instead, you encapsulate resource ownership within objects that manage the resource's lifetime. This is the RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) idiom. The "resource" (like heap-allocated memory) is "acquired" in the object's constructor and "released" in its destructor.This is what smart pointers (

std::unique_ptr: This is your default choice. It represents exclusive ownership of a resource. It's a lightweight wrapper that holds a raw pointer, but its destructor automatically calls delete on that pointer when the unique_ptr goes out of scope. This makes it impossible to leak the memory, even if an exception is thrown. It has zero-cost abstraction; it's the same performance as a raw pointer.std::shared_ptr: This represents shared ownership. It maintains an internal "control block" with a reference counter. When you copy a shared_ptr, the count increments. When a shared_ptr is destroyed, the count decrements. When the count reaches zero, the last shared_ptr standing automatically deletes the resource.std::weak_ptr: This is a non-owning companion to shared_ptr that breaks cyclical references. If two objects (e.g., Parent, Child) hold shared_ptrs to each other, their reference counts will never reach zero, and they will both leak. By making the Child's pointer to the Parent a std::weak_ptr, the child gets to observe the parent without contributing to its reference count, breaking the cycle.Mastering raw C-style pointers teaches you how the machine works. Mastering smart C++ pointers teaches you how to build robust, safe, and maintainable systems on top of that machine.